Black Canadians face systemic disparities and challenges rooted in historical racism,

discriminatory policies, prejudicial practices, and social biases, all of which continue to have a

wide range of impacts on this population (Williams et al., 2022). A comprehensive

understanding of the obstacles experienced by Black Canadians requires a clear definition of

racism, systemic racism, and discrimination followed by a discussion about the effects of these

phenomena on life outcomes.

Bonilla-Silva (1997) and Williams (2004) both provide definitions of racism that

contribute to this project. Collectively, the authors define racism as an organized social system in

which the dominant racial group, based on an ideology of inferiority, categorizes and ranks

people into social groups called “races” before subsequently devaluing, disempowering, and

differentially allocating valued societal resources and opportunities to groups defined as inferior.

Racism comprises four dimensions: interpersonal racism, internalized racism, institutional

racism, and structural racism. Interpersonal racism, the most well-known form, refers to racially

motivated interactions between individuals, while internalized racism involves the incorporation

of racist attitudes, stereotypes, prejudices, beliefs, and ideologies into a person’s worldview

(Schouler-Ocak et al. 2021). Institutionalized racism refers to the social and cultural forces,

institutions, ideologies, and processes that interact to create and reinforce inequalities between

ethnic groups. Finally, structural racism constitutes the social conditions that promote racial

discrimination through mutually reinforcing systems of housing, education, employment,

income, benefits, credits, media, healthcare, and criminal justice (Schouler-Ocak et al. 2021).

The impact of racism on the Black Canadian population extends far beyond individual

feelings and influences mental health, physical health, and life outcomes. Goosby et al. (2015)

examined the relationship between perceived discrimination and levels of C-reactive protein and

blood pressure in African American youth. Using face-to-face interviews and blood tests, the

authors found that the extent of perceived discrimination increases levels of C-reactive protein

and blood pressure. Other research has found that higher levels of c-reactive protein and blood

pressure have both been found in cardiovascular diseases posing risk to heart health and reducing

life expectancy (Hage, 2014). Another study by Korous et al. (2017) examined the relationship

between racial discrimination and cortisol output, finding that minorities often display

dysregulated cortisol secretion. Cortisol is a steroid hormone that fulfills a crucial role in the

body’s stress response system (Jones & Gwenin, 2021). Excessive or insufficient cortisol levels

pose a threat to an individual’s overall health, especially with the immune, metabolic,

cardiovascular, cognitive, and digestive systems (Jones & Gwenin, 2021). This research, in

conjunction, highlights the negative impact of racism on an individual’s physical health.

In addition, racism can detrimentally affect an individual’s mental health. In a meta-

analysis, Schmitt et al. (2014) examined the relationship between perceived discrimination and

psychological well-being. The authors found that individuals who interpret themselves as the

victim of racism can experience reductions in self-esteem and life satisfaction along with

depression, anxiety, and psychological distress, phenomena that concur with the Minority Stress

Theory. Moreover, exposure to racism throughout a lifetime can result in poorer health outcomes

through a process known as weathering, which refers to the progressive deterioration of health

for members of marginalized ethnic groups who endure long-term social and economic

disadvantages (Geronimo, 1992). Several authors examined the weathering effect and found that

the experiences of cumulative social and economic disadvantages, particularly in the areas of

employment, earnings, housing, and neighborhoods shaped by racism, constitute leading causes

of the weathering effect (Forde et al., 2019; Gee et al., 2019; Nazroo et al., 2020).

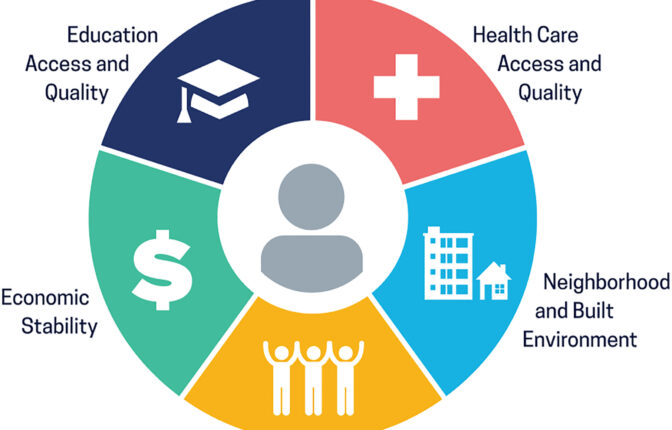

The Social Determinants of Health framework, first developed by Solar and Irwin (2010),

provides a solid foundation to explore and understand the experience of Black Canadians. In this

framework, the authors define four core domains that directly influence health outcomes: poverty

or food insecurity, education, employment, and housing. This framework is supported by another

theoretical perspective called the Social Integration Framework (Ager & Strang, 2008). This

model examines similar core domains that directly influence the way in which individuals

become integrated into a community: employment, housing, education, and health. According to

Ager and Strang (2008), these domains collectively contribute to health outcomes. Furthermore,

a Government of Canada (2020a) report on the social determinants of health for Black Canadians

examined key factors of systemic disparities faced by Black Canadians. In sum, this research

demonstrates many areas in which the Black population of Canada faces major health

inequalities, and the findings in each of these areas will be outlined in the sections below.

Poverty and Food Insecurity

Liu et al. (2023) define food insecurity as inadequate or insecure access to food resulting

from financial constraints. Poverty and food insecurity constitute strongly correlated factors as

Wight et al. (2014) demonstrated in their study that food insecurities mainly result from issues

pertaining to financial resources. Specifically, Wight et al. (2014) used the official poverty

measure (OPM) and the new supplemental poverty measure (SPM) to conduct their research.

The OPM, created in the 1950s, compares an individual’s or family’s resources to a set of

thresholds that represent the minimal income needed to support a family (Iceland, 2005). This

measure may vary depending on the size and makeup of the family. Individuals or families with

less than the required resources are deemed impoverished (Iceland, 2005). The SPM, created in

2010, includes family resources and needs as well as income from all sources, including cash

transfers; value of near-cash benefits; National Lunch Program; supplementary nutrition for

women, infants, and children (WIC); housing subsidies; and low-income home energy assistance

(LIHEAP) tax credits and payments, such as the EITC, minus necessary expenses for critical

goods and services not included in the thresholds (Wight et al., 2014). Wight et al. (2014) found

that incidences of food insecurity increase as the income-to-needs ratio decreases, thus

demonstrating a statistical significance in the relationship between poverty and household food

insecurity.

Furthermore, studies have found that in comparison to households of other ethnicities,

Black households with children experience the highest level of food insecurity (Sharanjit, 2023).

Other research performed by Statistics Canada (2020a) supports the idea of financial and food

disparities between Black and White Canadians. Between 2009 and 2012, studies found that in

comparison to White Canadians, Black Canadians were 2.8 times more likely to report moderate

or severe household insecurity with almost with almost four in ten (38%) reporting food

insecurity in 2023 (Government of Canada, 2020a; Sharanjit, 2023). In 2021, 12.4% of Black

Canadians, in comparison to 8.1% of the total population, lived in poor households (Statistics

Canada, 2023). Moreover, Schimmele et al. (2023) used Canada’s official poverty line to

examine generational differences in the poverty rate between 11 racialized groups and the White

population. Canada’s official poverty line emanates from the market basket measure (MBM)

thresholds, which are based on the cost of a specific basket of goods and services for a family of

two adults and two children. The basket measure contains qualities and quantities of food,

clothing, footwear, transportation, shelter, and other expenses, thus representing a basic and

necessary standard of living in a province for a specific year (Statistics Canada, 2015). Using the

MBM, Schimmele et al. (2023) found that the poverty rate of Black Canadians was 4.3

percentage points higher than that of the White population. This finding, along with the other

research in this section, indicates that due to the strong correlation between poverty and food

insecurity, Black Canadians, in comparison to White Canadians, consistently demonstrate an

increased likelihood of experiencing food insecurity.

Education

Research generally considers education as a major predictor of a healthier and more

meaningful life. As stated by the Government of Canada (2020a), education provides the

knowledge and skills required for life success as well as personal growth and development.

Despite the importance and beneficial nature of education, Black individuals living in Canada

face systemic barriers to accessing higher education and achieving academic success. The

Government of Canada (2020a) recounts that in 2016, Black women in Canada were 27% and

21% less likely than white women to complete high school and university respectively.

Moreover, Black youth, in comparison to other Canadian youth, demonstrate a lower likelihood

of obtaining a postsecondary degree (Government of Canada, 2020a). Lastly, the Government of

Canada (2020a) found that in comparison to students of other ethnicities, Black high school

students experienced a greater probability of being streamed into low-wage and applied

programs. This streaming occurred mainly due to negative stereotypes about Black Canadians as

well as lower expectations from teachers and school staff.

Employment

The quality of education generally constitutes a determining factor in an individual’s

employment opportunities and earning potential. Thus, the educational disadvantages that Black

Canadians experience also affect their employment prospects and status. In the 2016 census, the

Government of Canada (2020a) found that in comparison to their White counterparts, Black

women were almost twice as likely and Black men almost 1.5 times more likely to experience

unemployment in Canada. Moreover, 15.6% of Black adults and 10.7% of White adults work in

low-skilled occupations. Since these jobs generally lead to lower wages, Black adults

disproportionately experience employment disadvantages associated with position and salary.

Lastly, many Black individuals living in Canada face discrimination when applying for a job.

The Government of Canada (2020a) found that in comparison to candidates with African names,

applicants with Franco-Quebecois names were 38.3% more likely to obtain an interview. This

finding demonstrates the existence of systemic discrimination against individuals of African or

Black origin.

Housing

As one of the social determinants of health, housing affects the quality of life and

wellness for individuals. Specifically, poor-quality housing negatively impacts health and well-

being (Rolfe et al., 2020). Despite ongoing research outlining the importance of safe and secure

housing, in 2020, 20.6% of Black Canadians reported living in housing that cost more than they

could afford, while only 7.7% of White Canadians lived above their housing means (Government

of Canada, 2020a). Moreover, research reported that 12.9% of Black Canadians and only 1.1%

of White Canadians lived in crowded housing. A report from the Government of Canada (2020a)

found that in comparison to individuals of other ethnicities, Black individuals experienced a

higher likelihood of rejection from potential landlords. This result suggested that landlords and

other institutional factors contributed to systemic discrimination that reduced access to housing

for Black Canadians.

Criminal Justice System

The criminal justice system contributes to an individual’s integration within their

community as well as their health and safety. In comparison to other ethnicities, Black people

experience overrepresentation as both victims and accused criminals in Canada’s justice system.

The Government of Canada (2022b) found that Black individuals comprised 9% of offenders

under federal jurisdiction despite representing only 4.2% of the total Canadian population.

Moreover, the same source reported that in Ontario, Black adults constitute 5% of the adult

population while accounting for 14% of admissions to correctional services. Lastly, this report

found that in comparison to White individuals, Black individuals experience a higher likelihood

of incurring charges for drug use and possession (Government of Canada, 2022b). These

statistics provide ample evidence that racial profiling and inequitable treatment from law

enforcement disproportionately affects Black Canadians, leading to higher rates of incarceration

and the overrepresentation of this community in the justice system.

The publication of police brutality against Black individuals has encouraged a rise in

global awareness and advocacy against racial injustice. Specifically, news of police officers

injuring or murdering Black individuals in the United States has spurred global movements such

as Black Lives Matter. The Black Lives Matter Movement, founded by Alicia Garza, Patrisse

Cullors, and Opal Tometi, began in 2013 after a White police officer, George Zimmerman, killed

an unarmed black teenager, Trayvon Martin, and was acquitted for the murder (Black Lives

Matter, n.d). The movement became globally recognized after the killings of Michael Brown

(2014) and George Floyd (2020). Following these events, numerous videos surfaced on social

media, providing clear evidence of murder, which led to protests around the world. Despite this

heightened awareness, Black people in the United States and Canada still experience

disproportionate police brutality and murder relative to their population size (Crosby et al.,

2023).

Physical Health Inequities

Black Canadians experience inequities that lead to poorer health outcomes. This

population, in comparison to White Canadians, experienced a higher overall mortality rate

(Black Health Alliance, n.d). A report by the Black Health Alliance found that in comparison to

their White counterparts, Black individuals living in Toronto were three times more likely to

become infected or hospitalized with the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Moreover,

Statistics Canada (2022) found that the prevalence of diabetes among Black Canadians was 2.1

higher than that among White Canadians. Despite experiencing higher rates of chronic illnesses

and diseases, Black Canadians, in comparison to the general Canadian population, demonstrate

lower utilization levels of the healthcare system (Quan et al., 2006). These factors both fulfill a

major role in health inequities among the Black population in Canada.

Family doctors play a crucial part in assuring the delivery of comprehensive and

personalized healthcare as well as helping patients to navigate different resources that enable

improved health outcomes (Hellenberg et al., 2018). As the first point of contact for health

conditions, family doctors diagnose for a wide range of conditions and generally refer patients to

other specialists. While researchers agree about the importance of family doctors, Black

Canadians, in comparison to their white counterparts, demonstrate a lower likelihood of having a

family doctor and have experienced a ninefold lower rate of contact with general healthcare

providers (Siddiqi et al., 2017; Statistics Canada, 2022). The lack of doctors within the Black

Canadian population has a direct impact on the health of the community. For example, Olanlesi-

Aliu (2023) found that Black Canadians report the highest rate of heart disease and stroke, both

of which figure prominently among the most common causes of death in Canada.

Mental Health Inequities

The topic of mental health has evolved rapidly over the last few years in Canada, shaping

the country’s approaches to this crisis (Cosco et al., 2022). In Canada, mental health currently

comprises a crucial element of an individual’s general wellness, which affects quality of life,

relationships, productivity, physical health, and overall well-being. While Canada has exerted a

significant amount of effort into addressing the mental health of its citizens, the Black Canadian

population faces persistent challenges in accessing culturally sensitive mental health support and

resources. In comparison to their White counterparts, Black Canadians report poorer self-rated

mental health. For instance, Black Canadians experience rates of depression that rank six times

higher than those of the general Canadian population (Cénat et al., 2022). Despite experiencing

higher rates of mental health issues, Black Canadians use mental health services at only half the

rate of White Canadians (Chiu et al., 2018; Government of Canada, 2022; Fante-Coleman &

Jackson-Best, 2020). As in the case of physical wellness, Black Canadians face inequities in

service access and utilization as well as higher rates of mental health conditions.